Beach cleans rapidly and dramatically reduce plastic fragments released into the environment, according to the first scientific evidence of its kind.

Experts from Norce, one of Norway‘s largest research organisations, found that within a year of volunteers removing bottles, bags and other large pieces of plastic from the shore of an island near Bergen, the amount of microplastic on land and in the water fell by 99.5%.

The scientists believe high levels of UV in sunlight and warm temperatures in shallow water lead to a far more rapid degradation of plastic fragments than had previously been thought possible.

They say it should motivate a global effort to clean up coasts around the world.

Gunhild Bodtker, senior researcher at Norce, told Sky News: “I was happily surprised because it means the clean-up has efficiently reduced the leakage of microplastic into the sea. And that is really good news.

“Clean up plastic on the shores, clean up all the plastic in the environment. It really makes a difference.”

Sky News joined volunteers on a mass clean of plastic washed up in Hardanger fjord in Western Norway, one of the largest in the world.

TikTok fined €345m over handling of children’s data

NASA taking ‘concrete action’ to explore UFOs after landmark report

Why NASA report is significant – and what it means for search for extraterrestrial life

Its orientation means it acts as a giant funnel, collecting marine plastic swept by ocean currents from as far away as the UK, France and the Netherlands.

We found stretches of what the Norce scientists call “plastic soil” – a layer, up to 1m deep, of densely-packed fragments mixed with organic matter.

The microplastic pieces, which are less than 5mm in size, are likely to have been accumulating in the fjord for the last 50 years. They’re virtually impossible to remove.

Torgeir Naess, the mayor of Kvam municipality, was part of the year-long clean-up.

“When I used to come here as a little kid in the mid-1970s it was just a few ping pong balls and some bottles,” he said. “You can see now it has increased dramatically.”

But the new research strongly suggests that all is not lost. As long as large pieces of plastic are regularly removed, the fragments should begin to disappear.

That will only happen where the microplastic is exposed to the elements, scientists have said.

Plastic waste in deep, cold water could still take centuries to degrade.

Some of the submerged plastic is ‘ghost gear’ – lost fishing nets and pots that continue to trap and kill marine life.

Norwegian authorities are attempting to remove the abandoned gear.

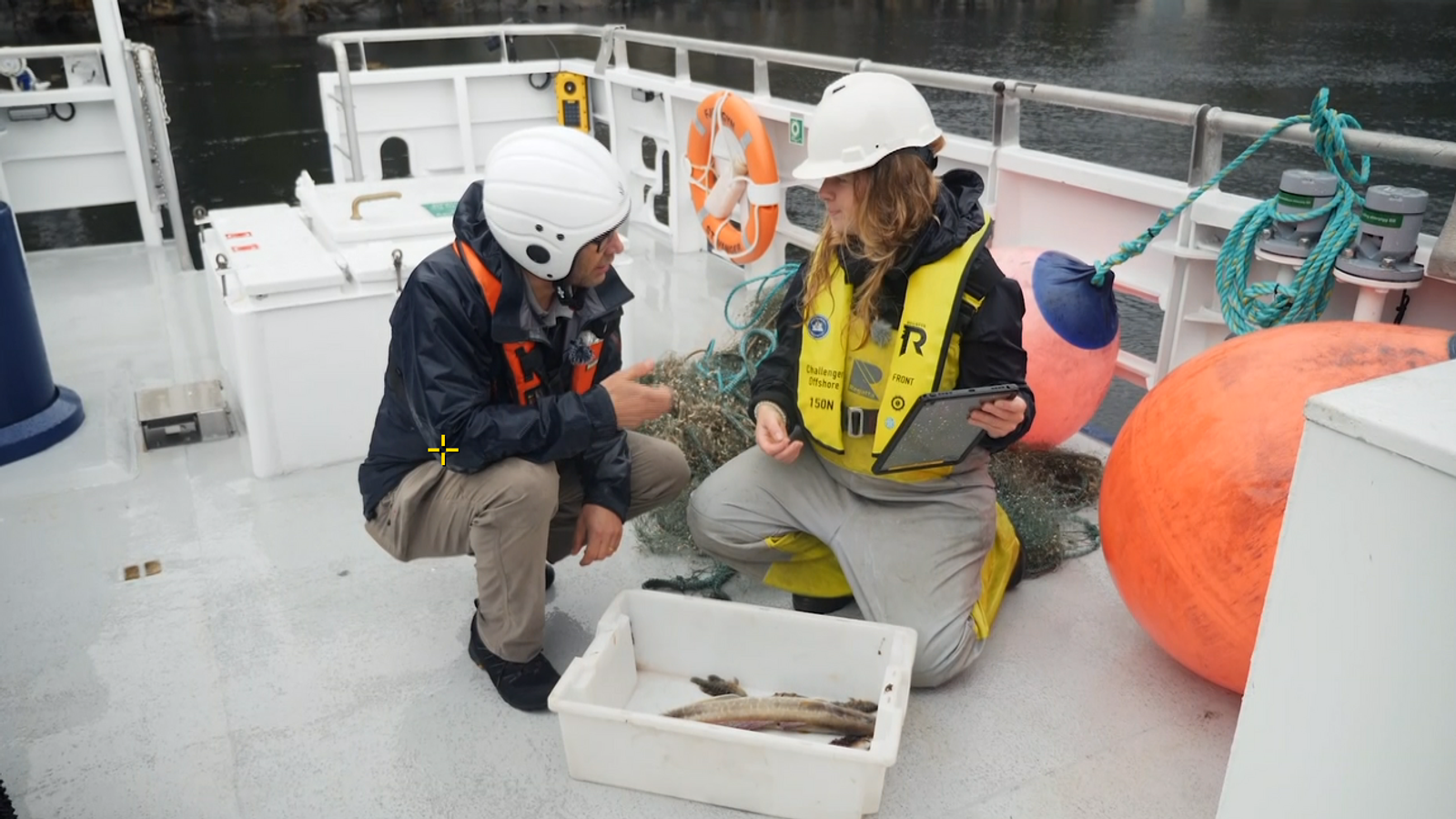

We watched a team use a remote-controlled submersible to hunt down a string of 10 pots lost by a fishing boat.

The pots were hauled to the surface, revealing a catch of fish, eels and even octopuses that would have died in a caged tomb.

Susanna Huneide Thorbjornsen, a scientist at the Institute of Marine Research, recorded the contents of each pot before releasing the marine life back into the fjord.

“The ghost fishing continues to harvest and it’s of no use to anyone,” she said. “It’s also an animal welfare issue – as well as plastic.”

More than 9,000 tonnes of plastic have been cleaned from Norway’s coast since the death of a whale in Bergen six years ago, its stomach stuffed with bags.

The death proved to be a tipping point for a nation and Sky News followed the story in an award-winning documentary.

Kenneth Bruvik, who has been leading the national clean-up, said: “The target is to clean the coastline completely.

“At the same time plastic will come back, but we will keep [levels] down and clean year by year.”

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Norway, along with Rwanda, is leading United Nations negotiations to agree a legally-binding Global Plastics Treaty to reduce production and pollution.

Another round of talks will take place in Kenya this November, with the ambition of it being in force in 2025.

But cleaning up the plastic pollution already out there also matters – and there’s now science to back it up.